Remind Me Again How Both Parties Are Basically the Same

In his first speech as president-elect, Joe Biden made articulate his intention to span the deep and bitter divisions in American social club. He pledged to wait beyond ruddy and blue and to discard the harsh rhetoric that characterizes our political debates.

It will be a difficult struggle. Americans have rarely been every bit polarized every bit they are today.

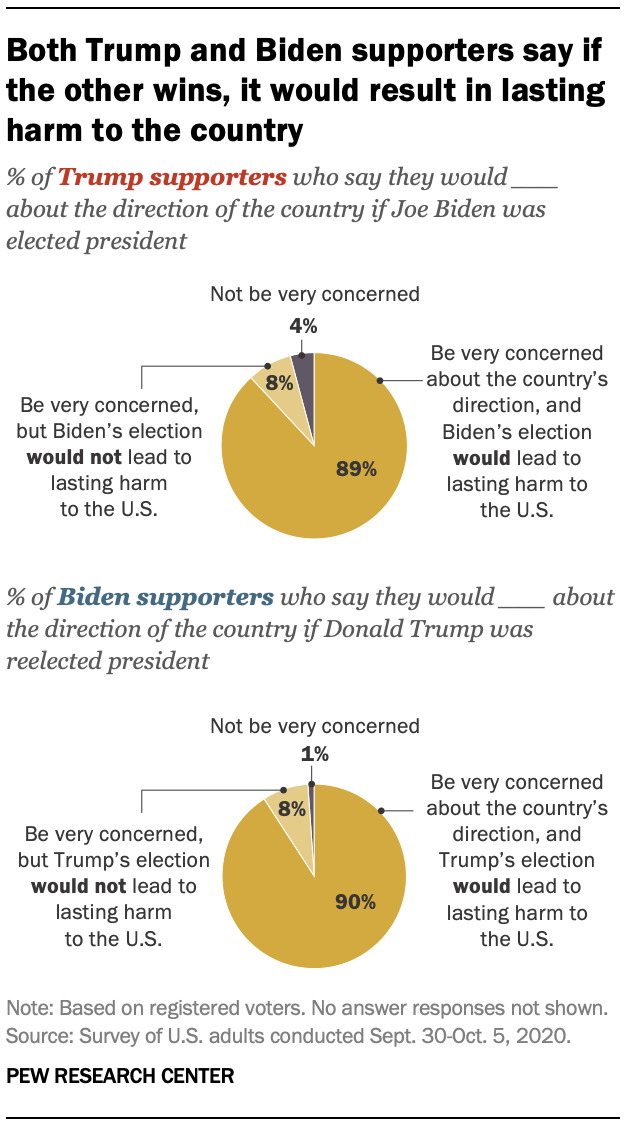

The studies we've conducted at Pew Research Center over the past few years illustrate the increasingly stark disagreement betwixt Democrats and Republicans on the economy, racial justice, climate change, law enforcement, international engagement and a long list of other issues. The 2020 presidential election further highlighted these deep-seated divides. Supporters of Biden and Donald Trump believe the differences between them are most more than just politics and policies. A calendar month before the election, roughly 8-in-ten registered voters in both camps said their differences with the other side were about core American values, and roughly nine-in-10 – once again in both camps – worried that a victory past the other would lead to "lasting harm" to the United States.

The U.S. is hardly the just country wrestling with deepening political fissures. Brexit has polarized British politics, the rise of populist parties has disrupted party systems across Europe, and cultural disharmonize and economical anxieties have intensified old cleavages and created new ones in many advanced democracies. America and other advanced economies face many mutual strains over how opportunity is distributed in a global economy and how our culture adapts to growing diversity in an interconnected earth.

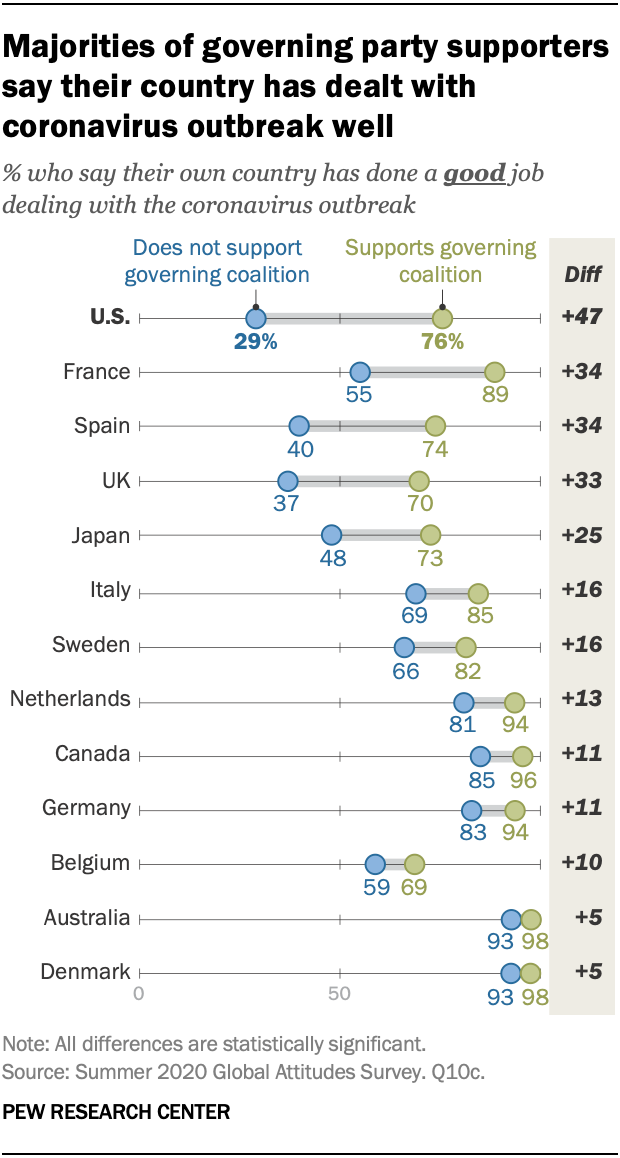

But the 2020 pandemic has revealed how pervasive the split in American politics is relative to other nations. Over the summertime, 76% of Republicans (including independents who lean to the political party) felt the U.S. had done a expert job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, compared with simply 29% of those who practice not identify with the Republican Political party. This 47 per centum point gap was the largest gap found between those who support the governing political party and those who do not beyond 14 nations surveyed. Moreover, 77% of Americans said the country was now more divided than before the outbreak, as compared with a median of 47% in the 13 other nations surveyed.

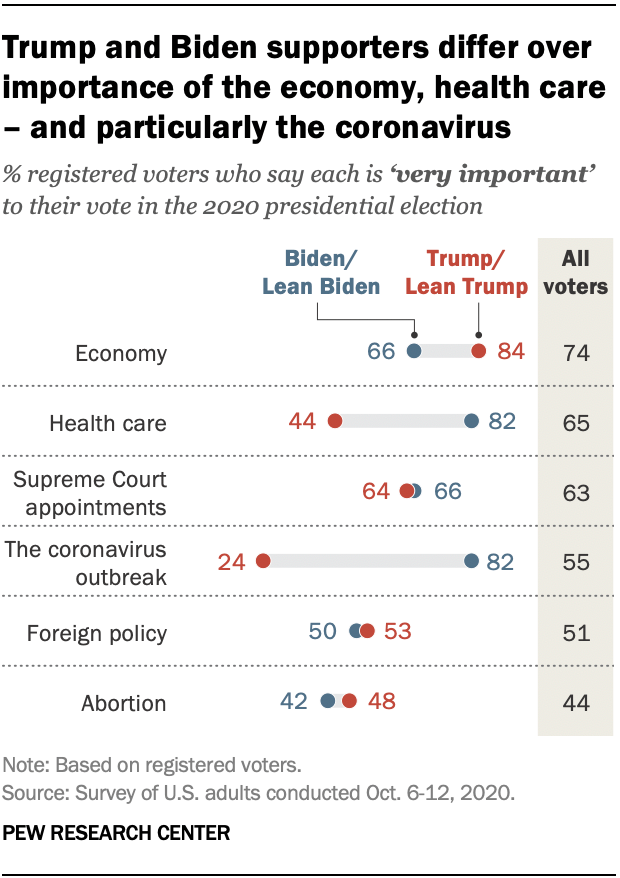

Much of this American exceptionalism preceded the coronavirus: In a Pew Research Eye study conducted earlier the pandemic, Americans were more ideologically divided than whatever of the 19 other publics surveyed when asked how much trust they have in scientists and whether scientists make decisions solely based on facts. These fissures have pervaded well-nigh every attribute of the public and policy response to the crisis over the class of the year. Democrats and Republicans differ over mask wearing, contact tracing, how well public wellness officials are dealing with the crunch, whether to get a vaccine once ane is available, and whether life volition remain changed in a major way after the pandemic. For Biden supporters, the coronavirus outbreak was a central issue in the election – in an Oct poll, 82% said it was very important to their vote. Among Trump supporters, it was easily the to the lowest degree meaning among six issues tested on the survey: Simply 24% said information technology was very important.

Why is America broken in this way? Once again, looking across other nations gives us some indication. The polarizing pressures of partisan media, social media, and even deeply rooted cultural, historical and regional divides are hardly unique to America. By comparison, America'south relatively rigid, two-political party electoral system stands apart past collapsing a wide range of legitimate social and political debates into a singular battle line that can make our differences appear even larger than they may actually be. And when the balance of support for these political parties is close enough for either to gain nearly-term electoral reward – as information technology has in the U.South. for more than a quarter century – the competition becomes cutthroat and politics begins to feel zero-sum, where one side'south gain is inherently the other'south loss. Finding common cause – fifty-fifty to fight a common enemy in the public health and economic threat posed by the coronavirus – has eluded united states.

Over time, these battles result in most all societal tensions becoming consolidated into 2 competing camps. As Ezra Klein and other writers have noted, divisions betwixt the ii parties have intensified over fourth dimension as various types of identities have become "stacked" on superlative of people's partisan identities. Race, religion and ideology at present align with partisan identity in means that they often didn't in eras when the 2 parties were relatively heterogenous coalitions. In their study of polarization across nations, Thomas Carothers and Andrew O'Donohue argue that polarization runs specially deep in the U.S. in part considering American polarization is "especially multifaceted." According to Carothers and O'Donohue, a "powerful alignment of ideology, race, and religion renders America'due south divisions unusually encompassing and profound. It is hard to find some other instance of polarization in the world," they write, "that fuses all three major types of identity divisions in a similar manner."

Of course, there's nothing wrong with disagreement in politics, and earlier nosotros become nostalgic for a less polarized past it's of import to remember that eras of relatively muted partisan conflict, such as the late 1950s, were also characterized by structural injustice that kept many voices – especially those of not-White Americans – out of the political loonshit. Similarly, previous eras of deep partitioning, such equally the late 1960s, were far less partisan but hardly less violent or destabilizing. Overall, information technology's not at all articulate that Americans are further apart from each other than we've been in the past, or even that we are more than ideologically or affectively divided – that is, exhibiting hostility to those of the other party – than citizens of other democracies. What's unique about this moment – and specially acute in America – is that these divisions accept collapsed onto a singular axis where we find no toehold for common crusade or collective national identity.

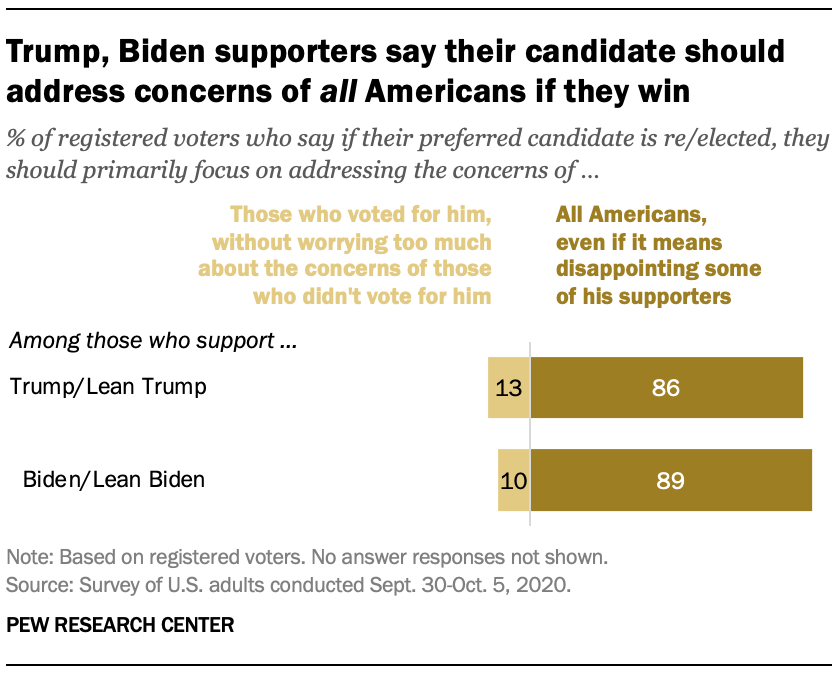

Americans both run into this problem and want to address it. Overwhelming majorities of both Trump (86%) and Biden (89%) supporters surveyed this fall said that their preferred candidate, if elected, should focus on addressing the needs of all Americans, "even if it means disappointing some of his supporters."

In his speech, President-elect Biden vowed to "work equally hard for those who didn't vote for me as those who did" and called on "this grim era of demonization in America" to come up to an cease. That's a sentiment that resonates with Americans on both sides of the fence. Just good intentions on the part of our leaders and ourselves face serious headwinds in a political organization that reinforces a ii-political party political battleground at most every level.

Richard Wike is director of global attitudes enquiry at Pew Enquiry Heart.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/13/america-is-exceptional-in-the-nature-of-its-political-divide/

0 Response to "Remind Me Again How Both Parties Are Basically the Same"

Post a Comment